June 06, 2013 1:00 PM

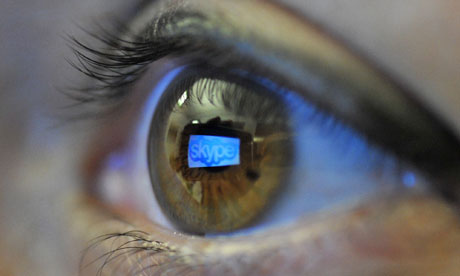

According to a top-secret court order obtained by The Guardian, the National Security Agency has collected the phone records of millions of U.S. Verizon customers since late April. The Guardian's Spencer Ackerman explains the coming debate over the scale of domestic spying operations.

Copyright © 2013 NPR. For personal, noncommercial use only. See Terms of Use. For other uses, prior permission required.

NEAL CONAN, HOST:

This is TALK OF THE NATION. I'm Neal Conan in Washington. Later in the program, we'll continue our series of conversations and look ahead with NPR's Deborah Amos, who's been covering the war in Syria. But we begin today with a court order obtained by The Guardian's U.S. team, which authorizes the National Security Agency to collect information on billions of phone calls made by U.S. Verizon customers since late April.

The order is unusually broad and has already inflamed controversy over civil liberties, the Patriot Act and the little-known court that authorized the data collection. Critics like the ACLU say there is no possible justification for such a sweeping search. The chairman of the House Intelligence Committee, Republican Mike Rogers, said today that phone records sweeps like the one reported today had stopped what he described as a significant terrorist against the United States within the past few years.

Spencer Ackerman, The Guardian's U.S. national security editor, joins us here in Studio 42. Thanks very much for coming in today.

SPENCER ACKERMAN: Thanks very much for having me.

CONAN: And since your story came out, we've had confirmation: A, that it's accurate; and B, that this kind of thing has been going on for, what, six or seven years.

ACKERMAN: For seven years is what members of Congress are now saying, raising the very interesting question of whether they knew precisely of the scope of metadata, so-called metadata collection that the NSA has been collecting.

CONAN: Well, let us inform ourselves. Metadata, what does that mean?

ACKERMAN: Yes, that's a great question. This gets a little jargony sometimes. Think of metadata as everything that isn't in the direct substance of our conversation, so not what it is that you and I are talking about right now but perhaps the mechanisms by which we are talking, the IP addresses, the phone numbers, the duration of the call, the frequency of interaction between us.

CONAN: So if you are collecting metadata, you might know that I called you at such and such a time, the call lasted so long, it was routed through these particular servers and that I called from Union Station, and you received it in – at Capitol Hill.

ACKERMAN: That's correct, and from that you can learn quite a great deal of identifying information about either ends of our phone call. I can find out particularly, if I look through other publicly available records, I can probably get your name, I can probably get your address, I can probably get your Social Security number, I can probably get your driver's license.

CONAN: If there's a TV camera up there, you could probably get my picture.

ACKERMAN: That's right.

CONAN: But you're being swarmed by billions of calls, maybe a billion calls a day. This is a three-month period. How do you sort through all that data?

ACKERMAN: You'll need essentially algorithms to determine when all that data is collected and tagged digitally, ultimately mechanisms like that for sorting through it. It's a tremendous amount of information.

CONAN: And computers sweep through it looking for particular patterns?

ACKERMAN: That's right.

CONAN: All right, so what can be gleaned from that information when there's so much of it?

ACKERMAN: Think about how often you talk to close associates, friends, people that you're related to, that you have longstanding connections with. That's the sort of thing I can infer from your call patterns based on the duration they take place and based on the frequency with which they take place. And when you're potentially investigating something, that information becomes rather important for understanding who someone that you might be collecting information on is talking to.

However, from the order that we acquired, there's no indication that they are in fact searching for anything specific. This is all potentially tens of millions if not more of information that goes across Verizon's pipes.

CONAN: And Verizon, they said today if such an order was issued, we're not allowed to talk about it. We are, however, had such an order been issued, required to comply with it and required not to say anything about it.

ACKERMAN: That's right. This order comes from a very secretive court called the FISA court. It's supposed to be the only judicial mechanism by which the government's surveillance efforts are checked. However, that court refuses to…

CONAN: Domestic surveillance.

ACKERMAN: Domestic surveillance, that's right. It refuses nearly no government requests. These orders occur in secret. What's called third party businesses and that sort of thing that are required to comply with it cannot publicly discuss the fact that they've been issued these orders.

The document that we acquired and we publish says that it cannot be declassified for another 30 years.

CONAN: And is there any reason to believe that all the other telephone companies aren't complying with similar orders?

ACKERMAN: I'd hate to speculate, but it would be very surprising.

CONAN: I wanted to read you some quotes from the White House spokesman, who is on a place with the president en route to California, I guess: The intelligence community is conducting court-authorized intelligence activities pursuant to public statute with the knowledge and oversight of Congress. That's according to Josh Earnest, traveling with the president to North Carolina.

An order relating to the collection of massive amounts of phone records made public, quote, "does not allow the government to listen in on anyone's telephone calls, nor did the information include the content of any communication nor the name of any subscriber."

ACKERMAN: Yes, but again when you learn the metadata around you, it's something of a cold comfort not to have your name attached to it because it's easily – it gives you quite a great deal of information as a basis for then finding that out. It's an open question.

CONAN: Now the timing of this, it was issued shortly after the bombing in Boston and the shootout that followed there. Is there any reason to believe it's connected with that?

ACKERMAN: I'd hate to speculate on that.

CONAN: OK, now that we know that these kinds of searches have been going on for the past seven years, and there have been hints about this from a couple of Democratic senators who have been complaining publicly but not allowed to say publicly what they were talking about until your report came out.

ACKERMAN: This is an interesting thing. In 2011, shortly before Congress took up the debate about reauthorizing the Patriot Act, I had an interview with Senator Ron Wyden, who is one of the Senate's premiere civil libertarians, and he told me that although he couldn't talk about publicly what in fact he was about to tell me that the government had an interpretation of its powers under the Patriot Act for surveillance that were far broader than what it had been saying publicly and what it expected Congress to vote on, that he considered this so important, that it was essentially a secret law, something substantially different from the public debate about the Patriot Act.

CONAN: And concern is not limited to Democrats on Capitol Hill. Early this morning, Republican Senator Mark Kirk of Illinois had Attorney General Eric Holder before him in testimony that had been previously scheduled, not called on this, but asked the attorney general about what he called the, quote, "Verizon scandal."

SENATOR MARK KIRK: Could you assure to us that no phones inside the Capitol were monitored of members of Congress that would give a future executive branch, if they started pulling this kind of thing up, would give them unique leverage over the legislature?

ATTORNEY GENERAL ERIC HOLDER: With all due respect, Senator, I don't think this is an appropriate setting for me to discuss that issue. I'd be more than glad to come back in an appropriate setting to discuss the issues that you have raised. But in this open forum, I don't…

KIRK: I would interrupt you and say the correct answer would be to say no, we stayed within our lane, and I'm assuring you we did not spy on members of Congress.

CONAN: And an appropriate forum, the attorney general's word, that means a secret session.

ACKERMAN: Yeah, I mean, I wonder if members of Congress are Verizon subscribers.

CONAN: Many possibly are, and it's interesting that this is coming from both sides of the aisle. Then of course you hear also from members of the intelligence committees, the people who were briefed on these operations, who are saying wait a minute, this has saved lives. These kinds of operations in the past have saved lives. These are authorized by the law, authorized by a court, this is perfectly legal, and we knew about it.

ACKERMAN: They have made that argument. It'll be interesting to see if there is any public disclosure that would substantiate that. It would also be interesting to find out if members of Congress even on those committees had the understanding of what in fact the scope of the surveillance they say they authorized was.

CONAN: Because if you were looking for certain phone numbers, certain individuals, it's a little easier to understand the intrusion. For billions of calls over a three-month period, it sounds like a giant fishing expedition.

ACKERMAN: And there's no reason to believe, when members of Congress are saying this has been happening for seven years, that that particular three-month period wouldn't have previously been reauthorized and won't be reauthorized in the future.

CONAN: So that there could have been a sequence of three-month authorization periods by the FISA court.

ACKERMAN: It's possible, given that this is what members of Congress are saying publicly about the length this surveillance has been occurring.

CONAN: Tell us a little bit about the FISA court. This is authorized again under a law by Congress.

ACKERMAN: That's correct. The 1978 foreign intelligence surveillance act, which is supposed to bind surveillance conducted by the government to ensure that individual Americans who are not suspected of any wrongdoing are not swept up in these rather broad and powerful government dragnets. It was a creation after some reforms by Congress in the 1970s to correct some abuses of the intelligence community.

And it operates entirely in secret. Members are appointed for I believe seven-year terms. And the scope of what they discuss is not adversarial. So the government pleads its case, but there's no one else, unlike elsewhere in the judicial system, to make counterarguments. And its decisions are almost never publicly known.

The scope of these decisions, we've now had reason to believe and now see, are very broad, and they almost never refuse a government request. In the last year, it had just come out publicly, they have I believe seen maybe something on the order of over 1,800 requests from the government for surveillance and refused none of them.

CONAN: And so as this goes ahead, the kind of controversy that's been generated today, do you think it is going to force the administration to be more forthcoming not only with what it's doing and why but what it has learned from these sweeps in the past?

ACKERMAN: We'll see.

CONAN: And as you go ahead, would you expect now that there would be public hearings about this?

ACKERMAN: Judging from the reaction in Congress, it's certainly possible. You've got a number of legislators, as you've pointed out, who are saying look, this is nothing new, nothing to see here, move along, and then others who are quite disturbed, particularly civil libertarian members of Congress that the government could be doing something like this for so many millions of Americans, potentially.

CONAN: And does this tie into the kinds of intrusive investigations that we've heard complaints about in recent weeks, as the administration has looked into phone records of reporters and various other issues?

ACKERMAN: Well, if they've looked into phone records of reporters, and now you've got a court order that shows that all subscriber data, that all communications that track over Verizon's pipes are collectable by the NSA, that in fact Verizon has to turn them over, I would be very interested to know how you could separate one from the other.

CONAN: Would you fear that your records might be looked into to find out who leaked you this document, this classified document?

ACKERMAN: I don't want to talk about that.

CONAN: Well, thanks very much, we appreciate your time today, and we will follow the story with interest.

ACKERMAN: Thanks very much.

CONAN: More on this story later today on ALL THINGS CONSIDERED. We were just speaking with Spencer Ackerman, national security editor for the British newspaper The Guardian, its U.S. unit. He joined us here in Studio 42. After a short break, NPR's Deb Amos joins us for the next in our series of looking ahead conversation. Syria is her beat. We'll be right back with her to talk about that country's future and how it may affect the entire region. Stay with us. I'm Neal Conan. It's the TALK OF THE NATION from NPR News.

Copyright © 2013 NPR. All rights reserved. No quotes from the materials contained herein may be used in any media without attribution to NPR. This transcript is provided for personal, noncommercial use only, pursuant to our Terms of Use. Any other use requires NPR's prior permission. Visit our permissions page for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by a contractor for NPR, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of NPR's programming is the audio.